Water helps assembly of biofibers that could capture sunlight

When it comes to water, some materials have a split personality – and some of these materials could hold the key to new ways of harnessing solar energy.

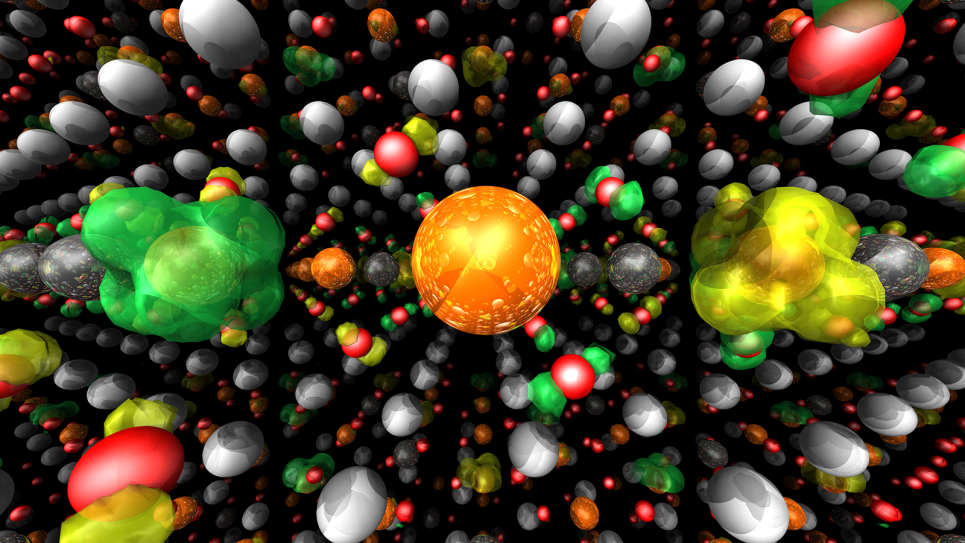

These small assemblies of organic molecules have parts that are hydrophobic, or water-fearing, while other parts are hydrophilic, or water-loving. Because of their schizoid nature, micelles organize themselves into spheres that have their hydrophilic parts turned out while their hydrophobic parts are shielded inside.

A new study from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE's) Argonne National Laboratory has shown water can serve another previously undiscovered role as these micelles coalesce to spontaneously form long fibers.

In a study led by Argonne nanoscientist Subramanian Sankaranarayanan and chemist Christopher Fry, both of Argonne’s Center for Nanoscale Materials, supercomputer simulations and as well as lab-based experiments showed that water serves as an invisible cage for the growth of the micelle fiber.

"Until now, trying to understand where the light-harvesting molecules bind has been like trying to see how a square peg can fit in a round hole.”

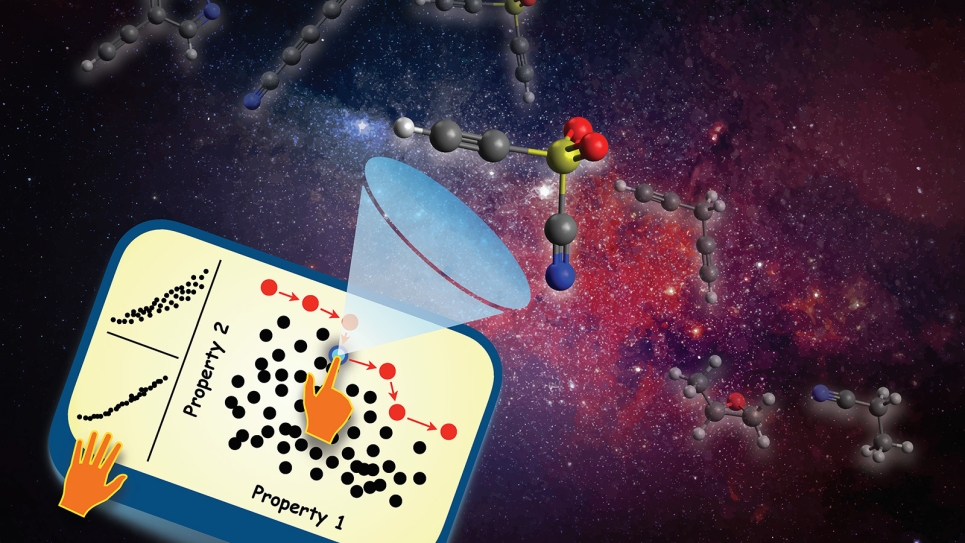

The study could help scientists to understand how light-harvesting molecules are incorporated into the micelle fiber as it assembles, which would be a key step to understanding some forms of artificial photosynthesis.

“Until now, trying to understand where the light-harvesting molecules bind has been like trying to see how a square peg can fit in a round hole,” said Sankaranarayanan. “By seeing the way in which the micelle fiber self-assembles, we can get a better understanding of how these kinds of light-harvesting systems are formed.”

Though micelles can be composed of several different types of organic molecules, the Argonne study specifically looked at those made of chains of amino acids. When micelles form, the water near the micelles becomes “strongly ordered,” which means that the water molecules are all oriented in the same manner. This strong ordering causes the formation of beta sheets, which are planar protein regions along which the micelle fiber grows.

In the experimental part of the study, Argonne chemist Christopher Fry used Sankaranarayanan’s computational findings to examine how a certain class of light-harvesting molecules known as zinc porphyrins could possibly become incorporated into the fiber.

“The results that came out of the simulations informed the areas I focused on in the lab,” Fry said. “I was able to probe some of the effects that water has on the overall self-assembly process, and that was something that we didn’t focus on in the lab before.”

“The water around the micelle stabilizes the structure, which enables the beta sheets to provide the platform for growth,” Sankaranarayanan added. “The more ordered the water becomes, the more stable the fiber becomes.”

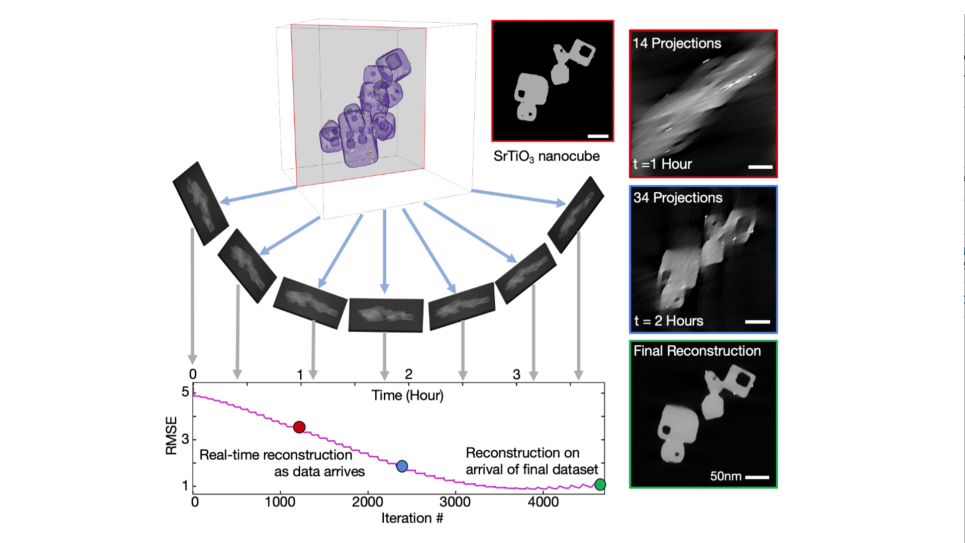

To effectively simulate the growth of the micelles and micelle fibers, Sankaranarayanan and his colleagues at the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility (ALCF) used two approaches to modeling on Mira, Argonne’s 10-petaflop supercomputer. They ran both coarse-grained simulations, which showed more general dynamics over relatively long periods of time, as well as atomistic simulations, which showed the motion of individual water molecules over very brief stretches.

“You need both of these views, and to be able to switch back and forth very quickly between them, in order to truly understand how the micelle fiber forms,” Sankaranarayanan said.

The researchers used the LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator) code to carry out the computationally demanding simulations. With help from ALCF staff, the team was able to achieve a 2x performance improvement on Mira by overcoming a performance bottleneck with the code’s ReaxFF module, an add-on package for modeling chemical reactions.

In collaboration with researchers from IBM, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Sandia National Laboratories, the ALCF’s code optimization efforts included adding OpenMP threading, replacing MPI point-to-point communication with MPI collectives in key algorithms, and implementing MPI I/O.

According to Fry, the next step of the research would involve using a template to assemble the fiber and the light-harvesting molecules simultaneously in such a way that they become naturally embedded in the fiber matrix. If successful, this advance could underlie improvements to organic components of some solar cells. “Can we make a material that would form part of a more efficient solar cell, that’s the question,” Fry said. “It’s all about being able to use a small peptide to tune the efficiency.”

Both the CNM and ALCF are DOE Office of Science user facilities.

A paper based on the study, “Water ordering controls the dynamic equilibrium of micelle-fiber formation in self-assembly of peptide amphiphiles,” appeared in the August 24 edition of Nature Communications.

The work was supported by the DOE’s Office of Science.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.