ALCF exascale computing and AI resources accelerate scientific breakthroughs in 2025

As 2025 comes to a close, we take look back at a year of groundbreaking research carried out by the ALCF user community.

In 2025, the Aurora exascale supercomputer began supporting open scientific research at the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility (ALCF), providing researchers with a powerful combination of simulation, AI, and data analysis capabilities to accelerate discoveries in science and engineering.

Researchers across disciplines used ALCF computing resources, including Aurora, Polaris, and the ALCF AI Testbed, to train billion-parameter AI models, run massive multiscale simulations, and develop new workflows that help bridge theory, computation, and experiment. The systems enabled breakthroughs in fields ranging from biology and materials science to cosmology and aircraft design. With multiple Gordon Bell Prize finalists and other high-impact results, ALCF users demonstrated how advances in exascale computing and AI are transforming science. The ALCF is a DOE Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory.

As 2025 draws to a close, we take a look back at some of the innovative research campaigns carried out by the ALCF user community this year. For more examples of the groundbreaking science supported by ALCF computing resources, explore the ALCF’s 2025 Science Report.

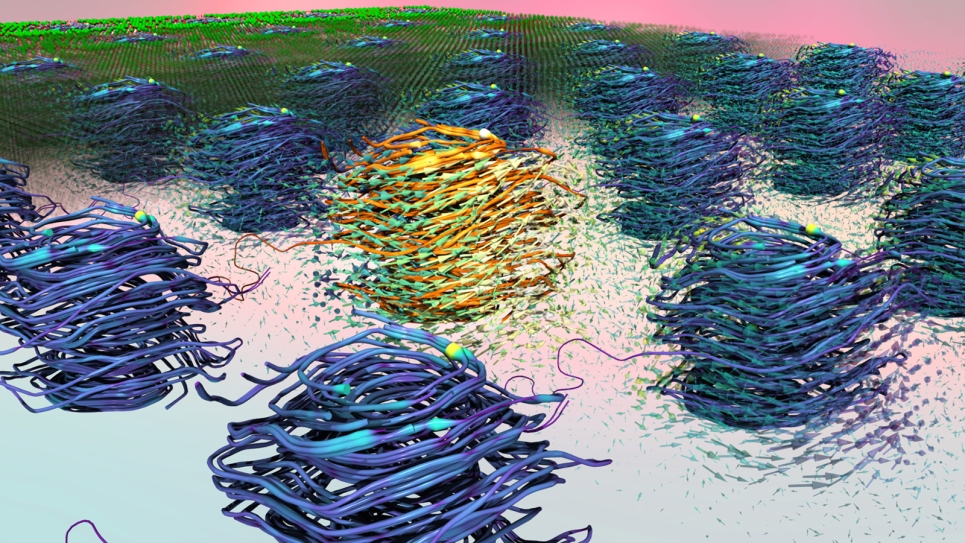

Simulating light-matter dynamics in unprecedented detail

Photo-switching of a ferroelectric nanoscale structure in lead titanate. (Image: ALCF Visualization and Data Analytics Team)

A team led by researchers from the University of Southern California (USC) used Aurora to run the largest simulations to date of light-matter interactions in quantum materials, modeling systems with more than a trillion atoms and achieving 1.87 exaflops of sustained performance. The team’s Multiscale Light-Matter Dynamics (MLMD) framework combined physics-based methods with AI (including the Allegro-FM foundation model) to accelerate atomic-scale predictions and extend those insights to larger-scale material behavior. The effort used a novel divide-conquer-recombine strategy to break the problem into smaller tasks, run each calculation on the GPU or CPU where it performed most efficiently, and then recombine the results, delivering speedups thousands of times faster than earlier methods. Their work aims to advance understanding of how light can alter quantum materials and offer insights that could guide the design of ultrafast, low-power electronic devices. The team's research was recognized as a finalist for the 2025 Gordon Bell Prize.

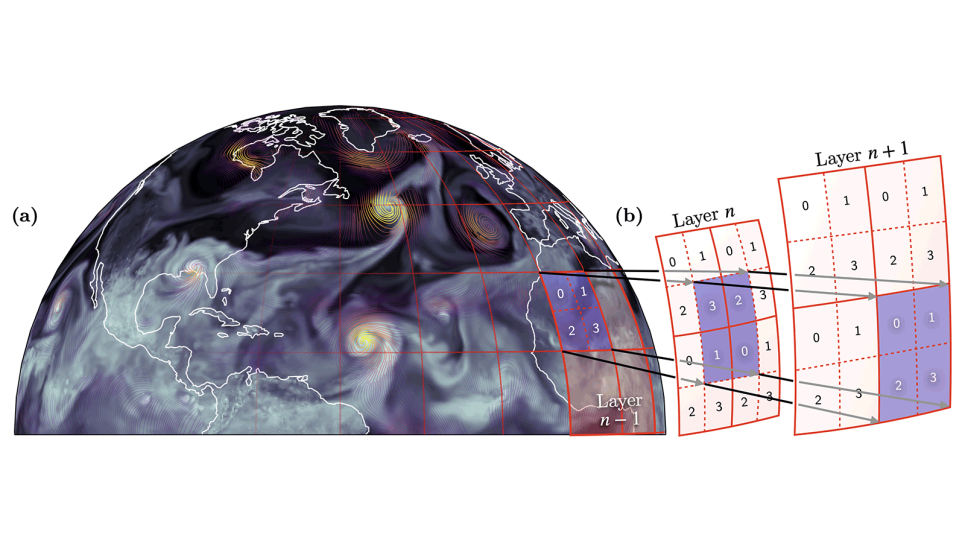

Building massive AI model to enhance forecasting capabilities

An AERIS-generated forecast of the Atlantic basin showing Hurricane Teddy, Tropical Storm Sally, and Post-Tropical Cyclone Paulette (a) and its sequence-window parallelism across network layers (b). (Image: Hatanpää et al., SC ’25 2025 (https://doi.org/10.1145/3712285.3772094))

The Argonne Earth Systems Model for Reliable and Skillful Predictions (AERIS) is a billion-parameter AI model designed to produce high-resolution forecasts beyond the range of traditional Earth system models. Built and trained on Aurora, AERIS reached more than 11 exaflops of mixed-precision performance and produced stable forecasts out to 90 days. To achieve this, the team developed a method called Sequence Window Parallelism (SWiPe). This approach efficiently distributes the model’s compute tasks and data across Aurora’s more than 60,000 GPUs while reducing communication between them. In tests, AERIS outperformed conventional models, showing the potential of AI models to improve subseasonal-to-seasonal forecasting. The team’s work was recognized as a finalist for the 2025 Gordon Bell Special Prize for Climate Modeling.

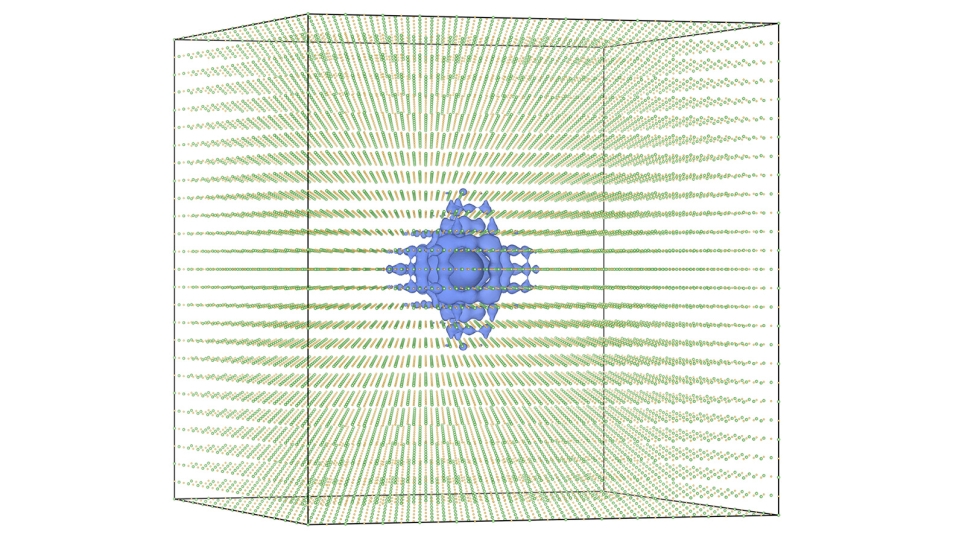

Enabling exascale simulations of quantum materials

Charge density of a defect state in a 17,574-atom lithium hydride (LiH) supercell. (Image: Chih-En Hsu, USC)

Researchers from USC and DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory used Aurora and other DOE supercomputers to enhance the performance of the open-source BerkeleyGW software, achieving new levels of accuracy in simulations of quantum materials. By extending the software’s capabilities, the team was able to couple electron and phonon interactions within a single framework to predict material properties with greater precision than traditional approaches. Aurora played a key role in the team’s research. Its large memory capacity and scalable architecture made it possible to carry out memory-intensive simulations of systems with tens of thousands of atoms. These runs allowed the researchers to capture quantum effects across larger and more complex systems. With the release of BerkeleyGW 4.0, these improvements are now available to the broader community. The team’s work was recognized as a finalist for the 2025 Gordon Bell Prize, reflecting a decade of work to adapt the code to modern GPU architectures.

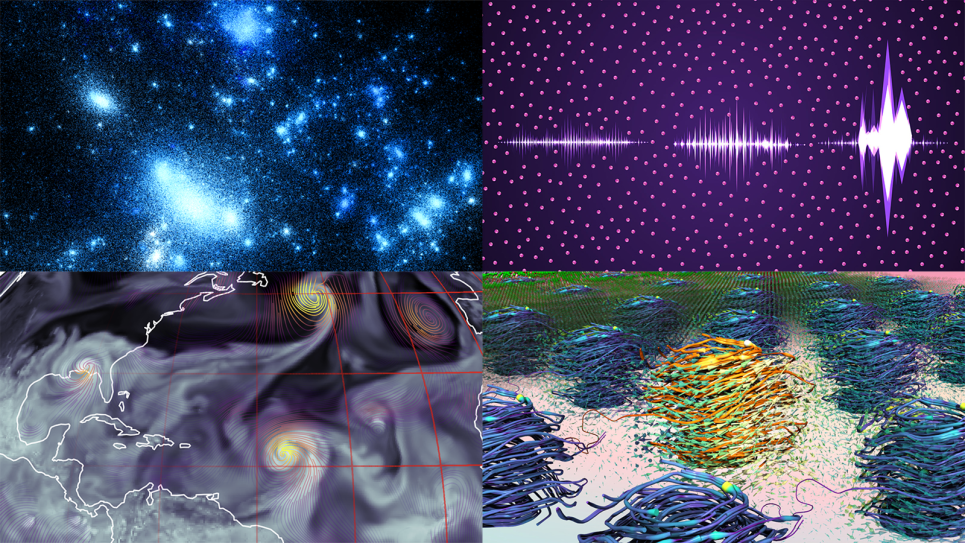

Shedding light on dark energy

Visual comparison of a small region in the simulations (left: standard model of cosmology; right: dynamical dark energy model). The differences are subtle but still clearly visible at the substructure level. Visual comparison of a small region in the simulations (left: standard model of cosmology; right: dynamical dark energy model). The differences are subtle but still clearly visible at the substructure level. (Image: ALCF Visualization and Data Analytics Team and the HACC Collaboration)

Argonne researchers used Aurora to run high-resolution cosmological simulations to investigate potential signs that dark energy may evolve over time, following notable first-year results from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI). The team carried out a pair of simulations—one assuming a constant cosmological constant and another with evolving dark energy—from identical initial conditions so they could track subtle differences as structure formed. Using on-the-fly analysis, Aurora allowed the team to perform large, high-resolution runs quickly, providing rapid insights to help disentangle potential new physics from observational or analysis systematics. The researchers made their high-resolution simulation data publicly available, providing a valuable testbed for the community to refine analysis techniques and explore new ways to interpret the results.

Improving next-generation aircraft with supercomputing and AI

This visualization shows airflow patterns over an aircraft’s vertical tail, highlighting how advanced simulations capture complex turbulence caused by rudder movement and air jets. (Image: Kenneth Jansen, University of Colorado Boulder)

A University of Colorado Boulder-led team is using Aurora to run large-scale simulations and machine learning models that aim to improve turbulence modeling and inform the design of more efficient aircraft. With Aurora’s exascale performance, the team is carrying out high-fidelity simulations of airflow around commercial aircraft components, including full-scale vertical tail and rudder assemblies. These simulations generate training data for new machine-learning-driven subgrid stress models that help capture small-scale turbulence effects in lower-resolution simulations. By combining Aurora’s power with software tools such as SmartSim and PETSc, the researchers are advancing techniques for online machine learning, real-time flow analysis, and virtual testing of aerodynamic designs that could reduce drag and fuel consumption. Their work supports long-term goals to reduce the need for costly wind tunnel and flight tests while enabling more accurate, scalable turbulence models for next-generation aircraft.

Turning materials data into AI-powered lab assistants

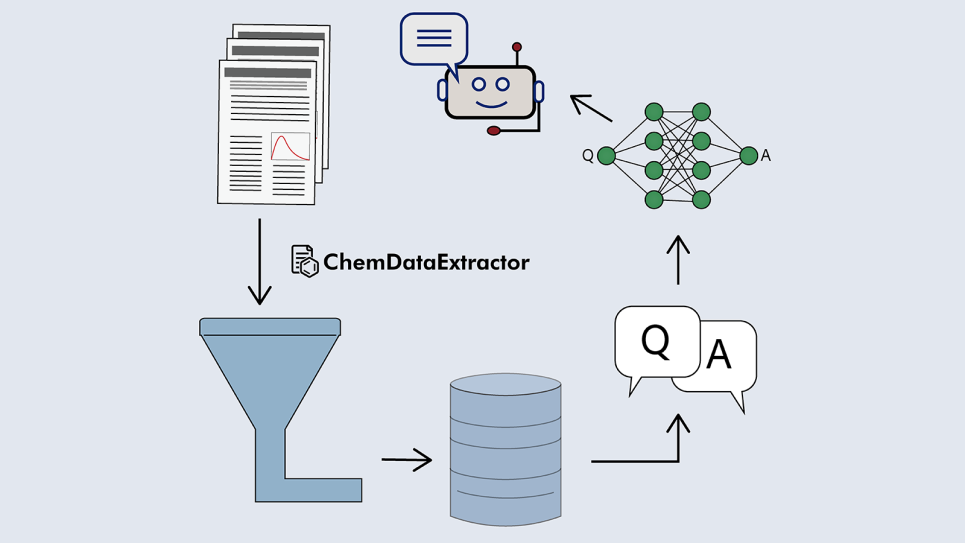

A schematic showing how scientific literature is mined using ChemDataExtractor to build materials databases. These databases are then employed to generate Q&A pairs, which are used to fine-tune efficient, materials-domain-specific language models. (Image: Mayank Shreshtha, University of Cambridge.)

Researchers from the University of Cambridge are using ALCF supercomputers to develop AI tools that extract structured materials data from scientific literature and convert it into domain-specific question-answering systems. Building on several years of research at ALCF, the team created extensive Q&A datasets using automated text-mining tools such as ChemDataExtractor, enabling smaller off-the-shelf language models to be fine-tuned without the costly pretraining process typically required for large language models. The smaller models match or exceed the performance of larger general-purpose models on domain-specific tasks while running at a fraction of the computational cost. In parallel, the team developed specialized language models, including MechBERT for mechanical properties, and built large stress-strain and photovoltaic materials databases to support broad areas of materials research. Together, these efforts demonstrate how AI and ALCF resources can streamline literature analysis, support experimentalists, and expand access to tools that help guide materials discovery.

Developing digital twins to advance next-generation nuclear reactors

Argonne's digital twin technology enhances nuclear reactor security and efficiency by using graph neural networks to predict reactor behavior in real-time. (Image by Shutterstock.)

Argonne researchers developed a new digital twin framework that uses graph neural networks (GNNs) to model and predict the behavior of advanced nuclear reactors with high speed and accuracy. By treating reactor systems as interconnected networks of components and embedding physics-based constraints into the model, the team created digital twins for both the historic EBR-II test reactor and a next-generation fluoride-salt-cooled high-temperature reactor. The researchers used ALCF computing resources to train the GNN models and perform uncertainty quantification, enabling rapid, reliable predictions that operate far faster than traditional reactor simulations. These GNN-based digital twins can anticipate how reactors respond to changes in power, cooling, and other operating conditions using only limited real-time sensor data. The approach supports real-time decision-making, anomaly detection, and long-range planning, offering a path toward safer and more efficient reactor operation.

Revealing atomic insights with new super-resolution X-ray technique

An incoming X-ray light wave (left) made up of a chaotic distribution of very fast spikes interacts with atoms (purple dots) in a gas to amplify specific spikes (right) in the light wave. (Image: Stacy Huang/Argonne National Laboratory.)

With support from ALCF computing resources, an international team developed a new X-ray spectroscopy method called stochastic Stimulated X-ray Raman Scattering (s-SXRS). The technique uses noise patterns from X-ray free-electron laser pulses to extract detailed information about the electronic structures of materials. This super-resolution approach enables ultrafast, high-detail snapshots of electron motion that were previously inaccessible, offering new avenues for studying chemical reactions and materials behavior. The team used ALCF resources to model and interpret the complex X-ray-matter interactions underlying s-SXRS, helping validate the technique and highlight its potential for chemical analysis and materials science. The method represents a significant step toward visualizing electron dynamics in excited states with greater clarity and precision.

Training AI foundation models to accelerate the discovery of new battery materials

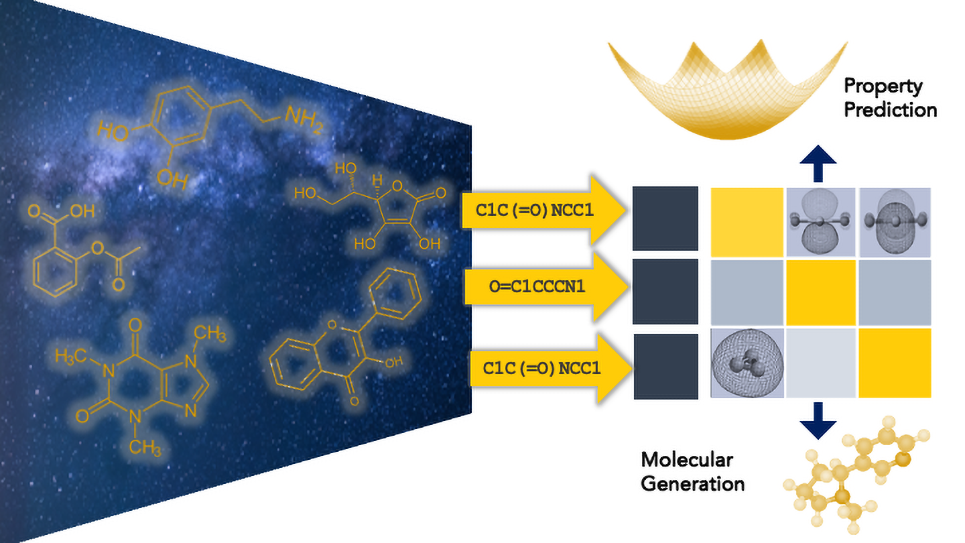

Researchers from the University of Michigan are using Argonne supercomputers to develop foundation models that accelerate molecular design and the discovery of new battery materials. (Image: Anoushka Bhutani, University of Michigan)

A University of Michigan-led team is using ALCF supercomputers to develop AI foundation models for battery materials discovery. Leveraging Polaris, the team built one of the largest chemical foundation models to date for electrolyte materials. To teach the model to understand molecular structures, they employed SMILES, a widely used system that provides text-based representations of molecules, and developed SMIRK, a new tool that improves how the model processes these structures, enabling it to learn from billions of molecules with greater precision and consistency. The foundation model unifies multiple prediction tasks and outperforms their prior single-property approaches, demonstrating the potential of supercomputing and AI to accelerate battery materials discovery. The researchers are now leveraging Aurora to build a second model focused on molecular crystals for electrode materials. Trained on datasets of billions of molecules, these models aim to help researchers explore vast chemical spaces and predict key properties for battery materials such as conductivity, melting point, and flammability.

Leveraging AI and exascale computing to revolutionize cancer research

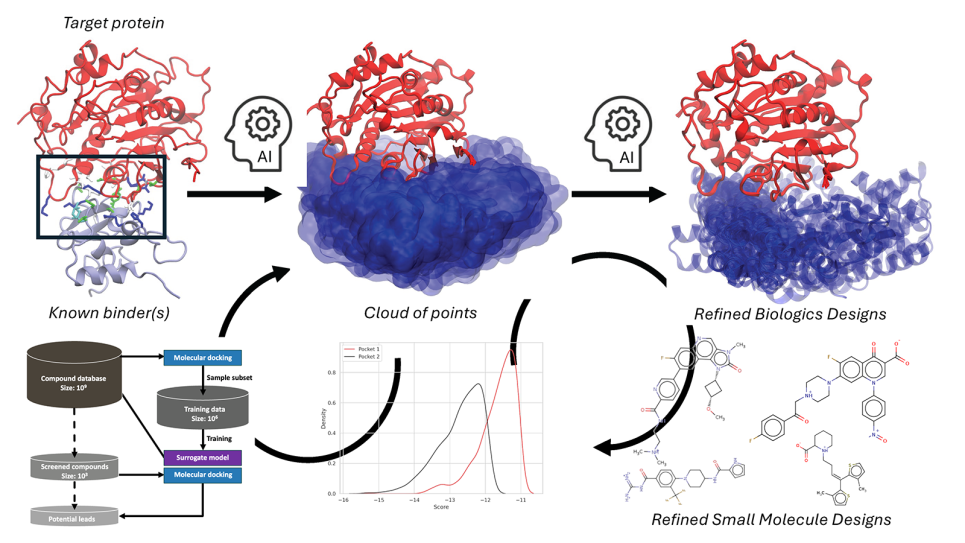

A schematic showing how small molecules and biologics are designed using scalable agentic workflows on Aurora. The method uses large training datasets to screen small molecules and peptides, while continuously optimizing the designs successively using diffusion models and molecular simulations. (Image: Archit Vasan and Arvind Ramanathan, Argonne National Laboratory)

Building on a decade of AI-driven cancer research, Argonne researchers used Aurora to scale AI methods for drug discovery and drug-response prediction, demonstrating the ability to screen vast numbers of molecules rapidly. The team screened 50 billion small molecules for potential cancer inhibitors in about 20 minutes on Aurora, a task that would have been impractical on earlier systems. The lab’s efforts also established frameworks for model evaluation and have expanded into a new effort, with the Integrated AI and Experimental Approaches for Targeting Intrinsically Disordered Proteins in Designing Anticancer Ligands (IDEAL) project targeting historically “undruggable” proteins by combining computational predictions with experimental data. Together, these activities illustrate how exascale computing, AI, and experimental collaborations can accelerate the discovery and testing of new drug candidates and improve confidence in predictive models.

Identifying new materials for quantum information storage

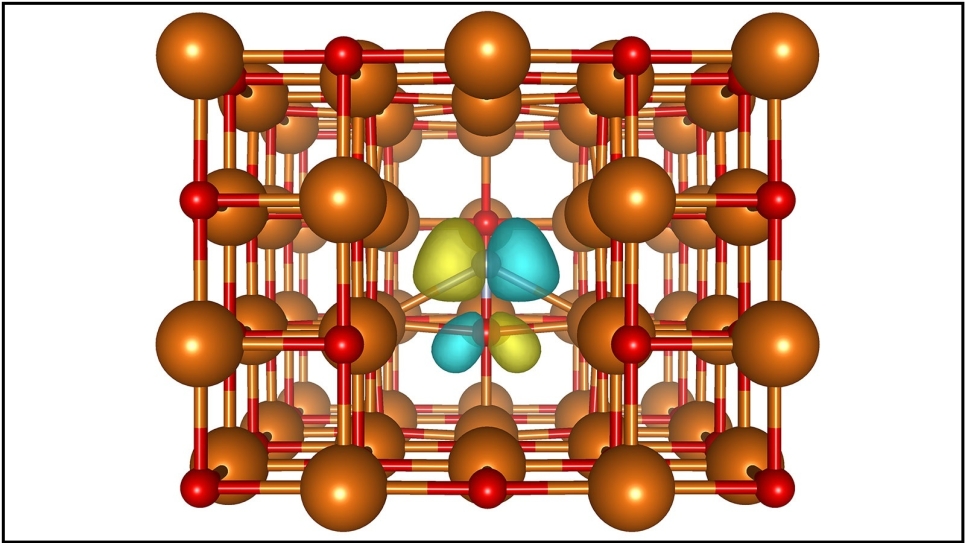

Magnesium atoms (orange) and oxygen atoms (red) surround the nitrogen-vacancy center in magnesium oxide, shown by a transparent representation of a nitrogen atom under the missing magnesium atom. The yellow and blue spots show how electrons localize around the vacancy.

Using DOE supercomputers, including ALCF’s Polaris, researchers performed high-precision calculations to identify a promising spin defect in magnesium oxide that could serve as a qubit for quantum technologies. By screening nearly 3,000 possible defects using high-throughput workflows, the team narrowed the field to candidates with desirable optical and spin properties and ultimately identified a nitrogen-vacancy center as the most viable option. The researchers then applied advanced electronic-structure methods, using software developed by the Midwest Integrated Center for Computational Materials, to characterize the defect’s optical behavior and interactions with the surrounding magnesium and oxygen atoms. These calculations provide a detailed picture of the defect’s properties and offer guidance for future experimental synthesis. The results found that magnesium oxide, a widely used industrial material, could be a strong candidate for qubit development and open the door to exploring additional spin defects in oxide hosts.